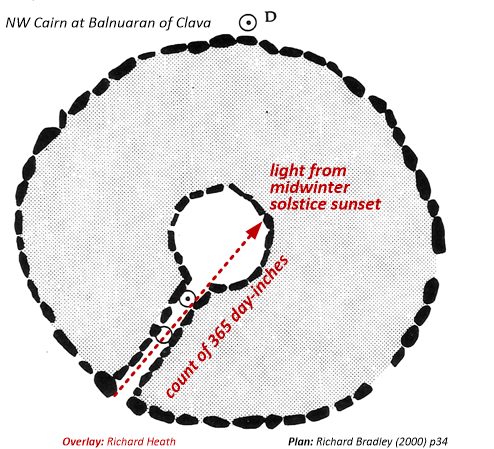

In North East Scotland, near Inverness, lies Balnuaran of Clava, a group of three cairns with a unique and distinctive style, called Clava cairns; of which evidence of 80 examples have been found in that region. They are round, having an inner and outer kerb of upright stones between which are an infill of stones. They may or may not have a passageway from the outer to the inner kerb, into the round chamber within. At Balnuaran, two have passages on a shared alignment to the midwinter solstice. In contrast, the central ring cairn has no passage and it is staggered west of that shared axis.

This off-axis ring cairn could have been located to be illuminated by the midsummer sunrise from the NE Cairn, complementing the midwinter sunset to the south of the two passageways of the other cairns. Yet the primary and obvious focus for the Balnuaran complex is the midwinter sunset down the aligned passages. In fact, the ring cairn is more credibly aligned to the lunar minimum standstill of the moon to the south – an alignment which dominates the complex since, in that direction the horizon is nearly flat whilst the topography of the site otherwise suffers from raised horizons.