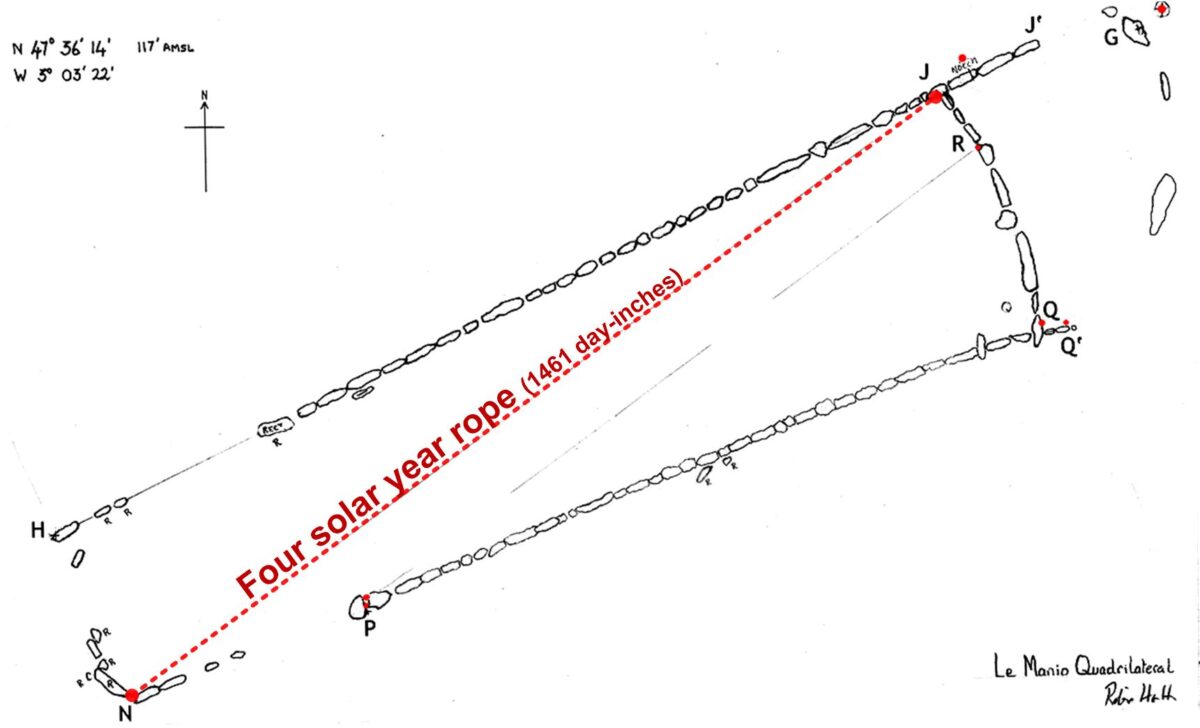

above: Le Manio Quadrilateral

This series is about how the megalithic, which had no written numbers or arithmetic, could process numbers, counted as “lengths of days”, using geometries and factorization.

My thanks to Dan Palmateer of Nova Scotia

for his graphics and dialogue for this series.

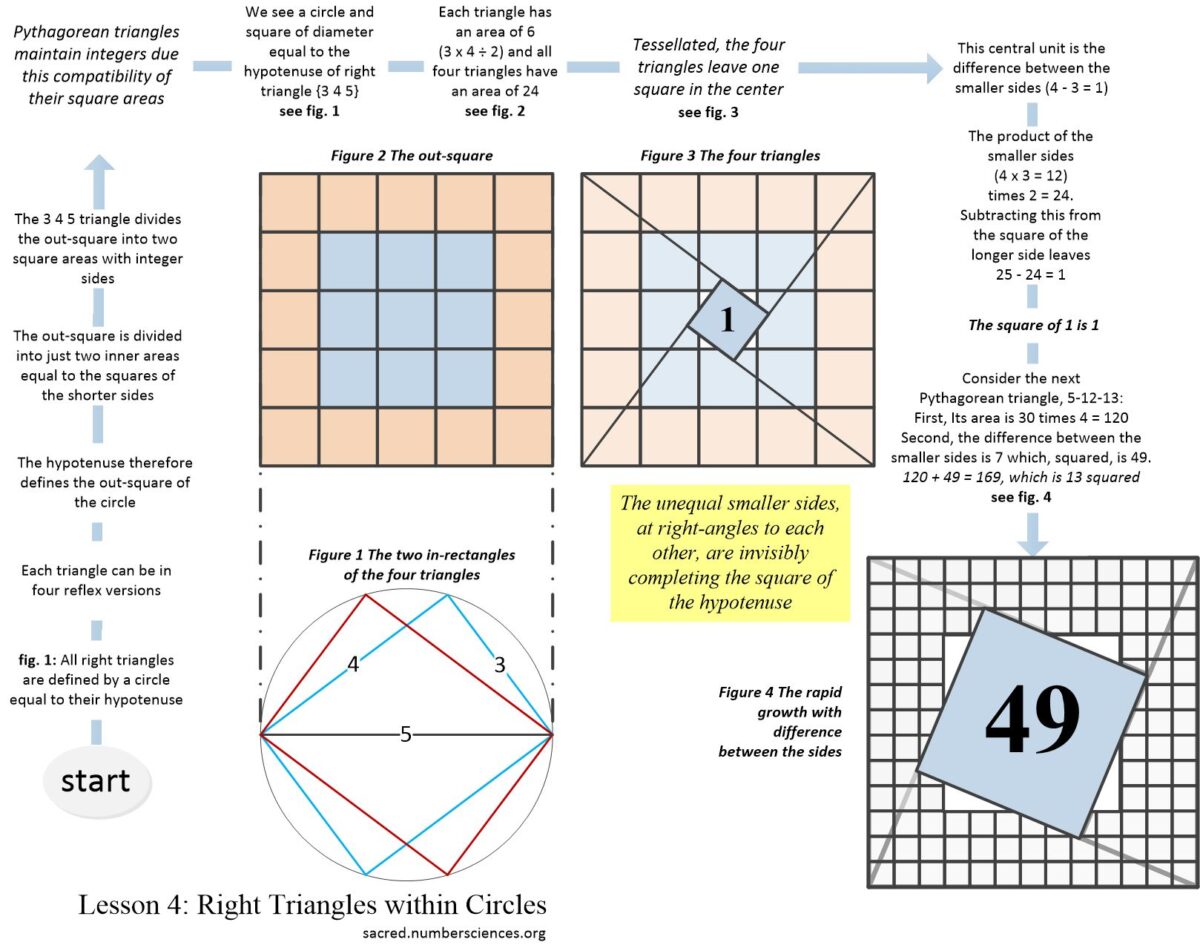

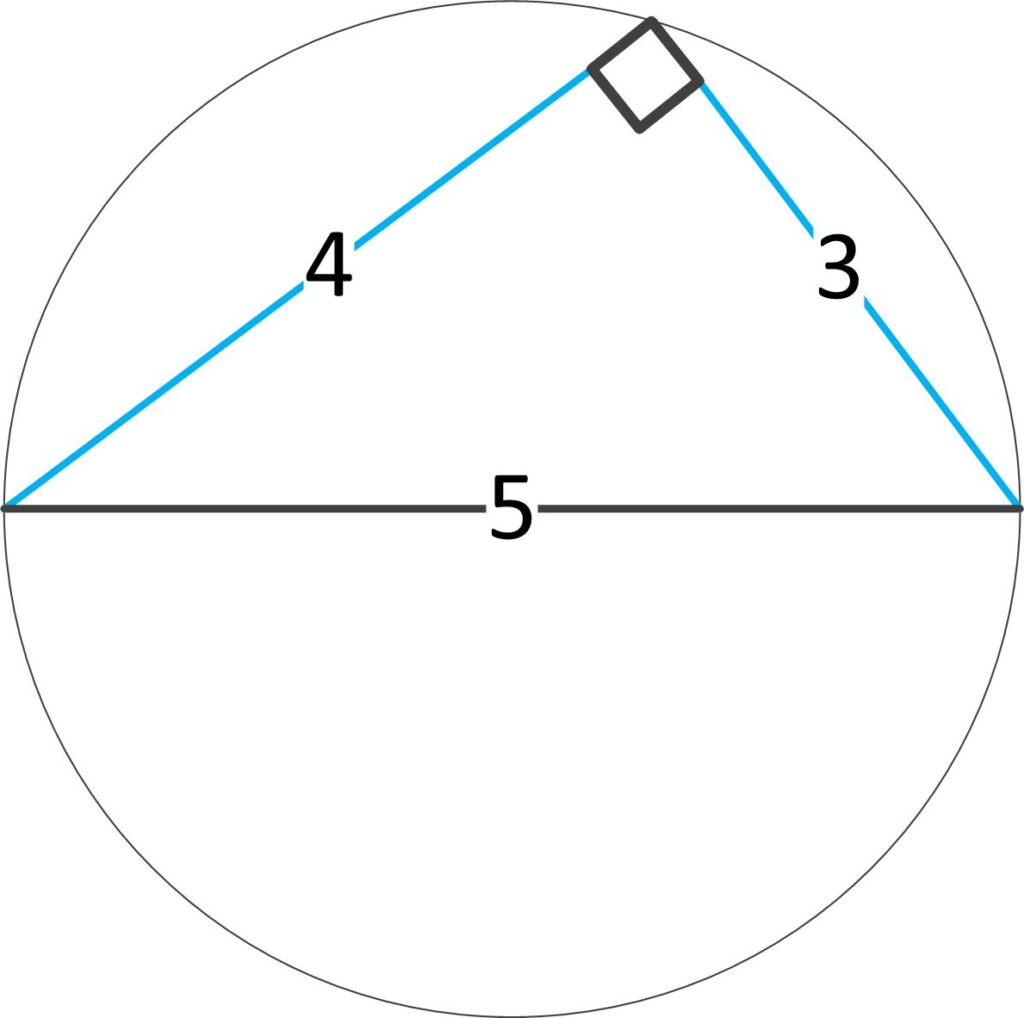

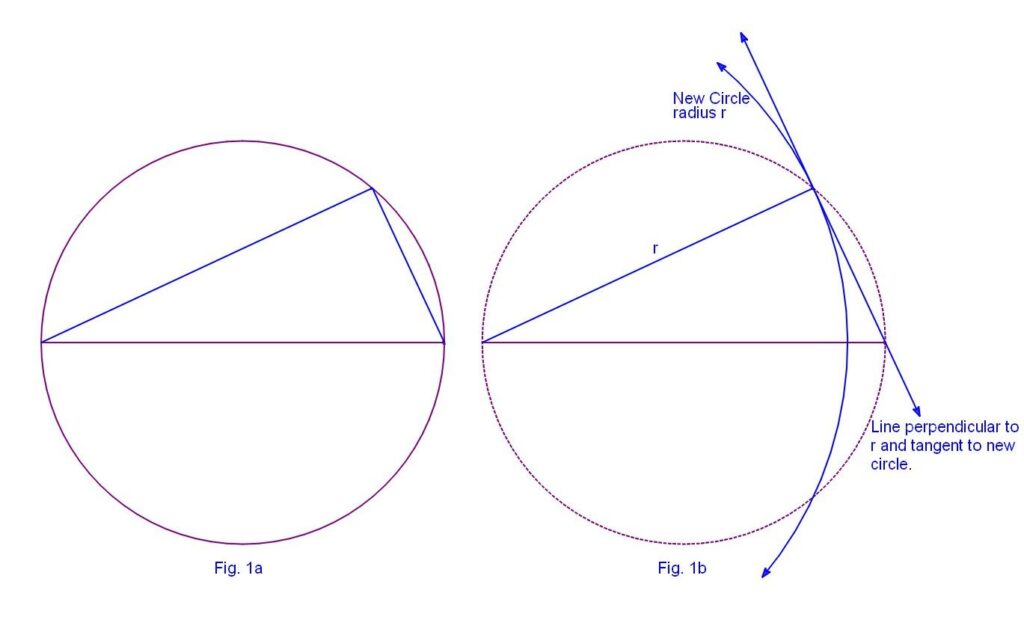

The last lesson showed how right triangles are at home within circles, having a diameter equal to their longest side whereupon their right angle sits upon the circumference. The two shorter sides sit upon either end of the diameter (Fig. 1a). Another approach (Fig. 1b) is to make the next longest side a radius, so creating a smaller circle in which some of the longest side is outside the circle. This arrangement forces the third side to be tangent to the radius of the new circle because of the right angle between the shorter sides. The scale of the circle is obviously larger in the second case.

Figure 1 (a) Right triangle within a circle, (b) Making a tangent from a radius.

Continue reading “Geometry 5: Easy application of numerical ratios”